Why alternative proteins need the non-profit sector

8 minute read - October 23rd 2024

Imagine a world where cultivated and plant-based meats are not only affordable but just as delicious and accessible as conventional meat. In this world, the demand for factory-farmed products plummets, ushering in a food system that's kinder to animals, people, and the planet.

ChatGPT’s depiction of this potential future

This is one of the potential paths to beating factory farming, and at first glance, it seems like profit-driven companies should be able to make this vision a reality on their own. After all, the reason solar and wind energy are being rolled out at massive scale today is simple: There is a profit motive, and the economics work.

So why do alternative proteins need non-profit support?

The answer is that even the most promising innovation faces obstacles on the road to growth – and that includes solar and wind! First, we need to level the playing field so that for-profit alternative protein companies have a chance to compete and win. Second, we need to provide the kind of additional support that many of the most beneficial technologies need to reach large-scale adoption. Finally, we need to address the market failures that hold back much needed innovation.

To get to the bottom of this, we’ll need to go back to economics 101. Let's explore the crucial roles for non-profits in making alternative proteins thrive.

The Challenge: An Uneven Playing Field That Needs Rebalancing

Despite the potential of alternative proteins, they face significant obstacles in competing with traditional animal products. Not only is the current playing field uneven, but there's a strong case to be made that it should be intentionally tilted in favor of alternative proteins. Why? Because pro-social technologies often need extra support to reach commercial adoption, as we've seen with solar, wind, and electric vehicles.

ChatGPT’s confusing depiction of superhero (i.e. the charity sector) helping alternative proteins climb a mountain (i.e. reach scale)

This imbalance manifests in four key areas:

1) Investment Disparities

- Only 3% of the EU and US research and innovation budget for protein sources went to alternative proteins between 2014 and 20201

- Public spending on production and commercialization heavily favors meat and dairy industries2

- Alternative proteins, at a critical stage in their development, require substantial investment to reduce costs, while traditional protein sources are mature industries that can largely self-fund

2) Regulatory obstacles

Alternative proteins face numerous regulatory barriers:

- Restrictive labeling laws in the EU limit the use of terms like "milk" and "cheese" for plant-based products3

(For those who agree with this decision on the grounds that ‘oat milk isn’t technically milk’, I’d like to point out how often we use functional rather than technical definitions for words. If someone corrected an adopted child calling their adoptive parent “dad” because they’re not technically their parent, the technical term for that person would be “asshole”) - Both the EU and the U.S. have made additional legislative attempts to restrict the labeling of meat and dairy substitutes

4

. - Some regions have outright bans on lab-grown meat, including Florida5

, Alabama6 and Italy7 . Similar proposals have been made in other countries, like France8

Ironically, it’s often the same groups that oppose regulating factory farming to ban the cruelest practices by appealing to the importance of the free market that support regulatory restrictions on alt proteins.

This summary from an academic journal shows how the deck is stacked against alternative proteins

Besides cases where regulation explicitly blocks alternative proteins out, many governments make it very difficult to rule them in: For example, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) approval process for novel foods is lengthy and complex, potentially taking years.9

3) Information failures

The third reason the market is failing to deliver the food system innovation we need at scale is information failures: The modern consumer is very divorced from where their food comes from.

This is partially due to urbanization which means that most of the population lives far away from where most farming happens.

However it’s also by design, with the many factory farming facilities located near residential areas made to be deliberately inconspicuous. As Paul McCartney pointed out, if slaughterhouses had glass walls, people would feel very differently about where most of our meat comes from today.

Meanwhile, the image painted of factory farms by the industry’s marketing tells us a blatantly false story, but one that we have a strong incentive to believe, as wilful ignorance of where our food comes from is far more comfortable than confronting reality.

As a result of being misinformed about how our animals are raised, consumers aren’t factoring the full cost of factory farmed meat to animals, to human health and to the environment into their purchase decisions. We can’t rely on the market to make sure the better products succeed when people aren’t able to make informed choices.

4) Externalities

The final barrier to alternative proteins competing on an even-playing field is externalities, a type of market failure where the full costs or benefits of a product aren’t being built into its price. We’ve seen this in the energy sector, where the price of coal-powered electricity is lower than it would be if the fossil fuel companies had to pay to prevent or fix the environmental and economic damage they create by driving climate change. In the case of the food system, the price of factory farmed meat doesn’t reflect the cost society pays through increased pandemic risk, accelerated climate change and the suffering of billions of animals that don’t get to participate in the free market.

The Goal: Supporting Beneficial Technologies to Scale

It’s a problem that alternative proteins don’t get to compete on a level playing field. The factory farming industry has stacked the deck. But I’d argue that the goal isn’t just to level the playing field, but to shift the advantage in the other direction.

There are plenty of technologies that would clearly benefit society if they reached scale, and could be commercially viable and self-sustaining once they get there. But we can increase the chances that they overcome the ‘technology valley of death’ and the speed at which they traverse it, by actively supporting them.

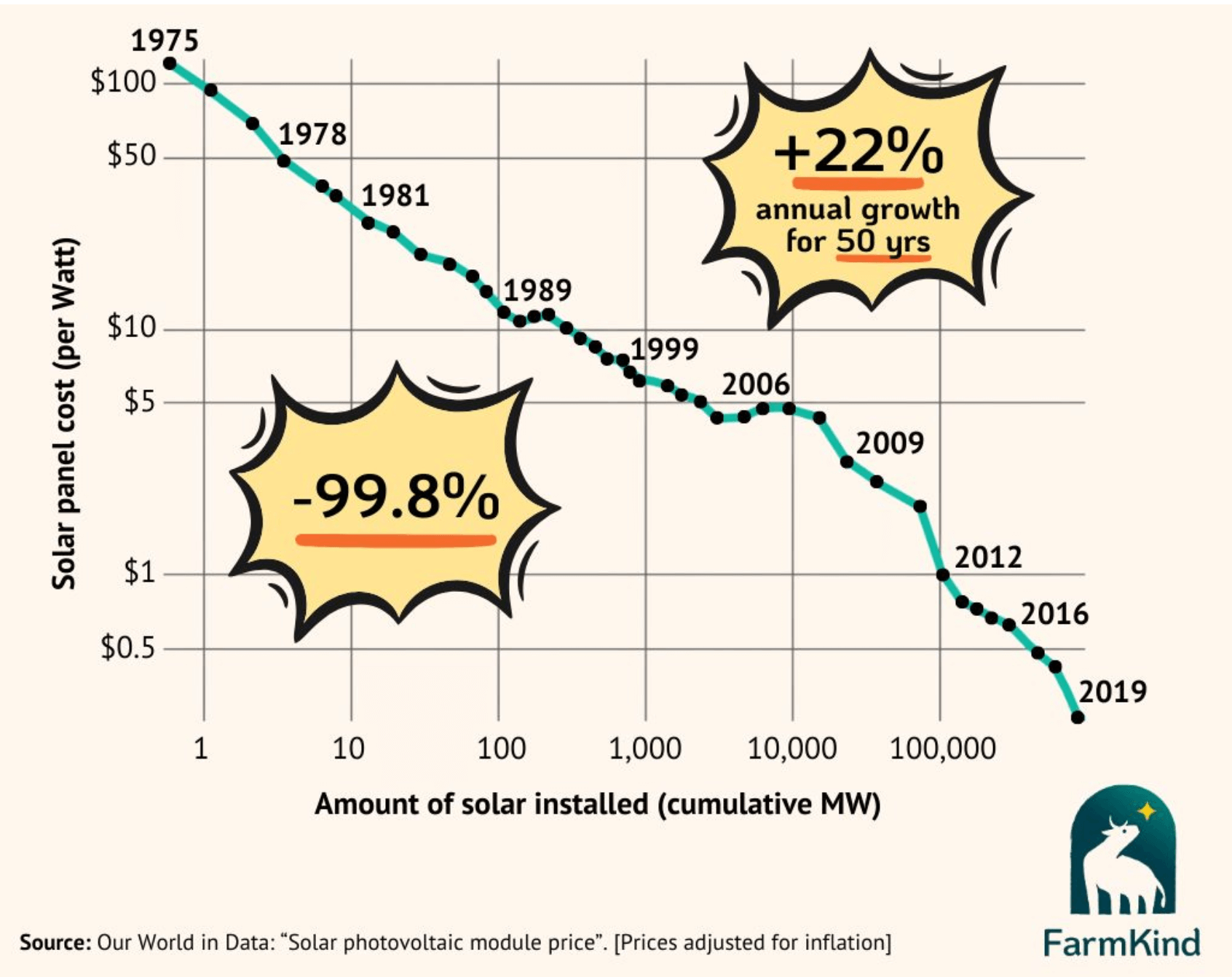

Renewable energy is the perfect example. Early for-profit investments in solar would just not have made money, but now it’s a thriving industry that’s turning the tide on climate change. Thanks to government subsidies early in the industry’s development, they were able to scale production, driving costs down by over 99% and causing the exponential growth in adoption.12

Imagine how quickly things could progress if alternative proteins received more government support!

The Solution: Non-Profit Intervention

Non-profit organizations are the missing piece of the puzzle that helps to level the playing field and support beneficial technologies to scale. They contribute in three main ways:

1. Government Advocacy and Policy Work

Non-profits like the Good Food Institute (GFI) and Dansk Vegetarisk Forening (DVF) work to:

The secretary general of DVF advocating for a plant-based future at an event.

- Convince governments to invest more in alternatives to meat and dairy (e.g. DVF lobbied the Danish government to establish a $100 million fund for plant-based initiatives).13

- Challenge unfair regulations14

, push for fair approval processes15 and guide startups through the tedious existing approvals process (e.g. GFI does this in the EU) - Counter the lobbying efforts of traditional animal agriculture industries.

2. Research and Development Support

3D-printed plant-based steak, from Redefine Meat (it’s really tasty!)

- Providing tools to make innovation easier, like databases of research ideas, grant opportunities and startup jobs 18

3. Public Education and Awareness

The Humane League bringing awareness to cruelty in McDonalds’ supply chain

Animal welfare charities like The Humane League and Sinergia Animal go undercover to take footage of factory farms and speak out publicly about the true costs of factory farmed products to animals, people and the environment. This can help to rectify the market failure of consumers making choices without complete information. While the cost-effectiveness of these kinds of social media awareness campaigns has been debated19,

Navigating Challenges and Future Prospects

The commercialisation of alternative proteins cannot be achieved by the private sector alone. Governments are already exerting influence over the industry, but too often for the worse. Non-profit organizations play a crucial role in filling the private sector gaps and nudging government to use their influence more wisely.

By supporting these non-profit efforts, we can accelerate the transition to a world where alternative proteins are as affordable, accessible, and appetizing as conventional meat, eggs and dairy.